How does endometriosis affect women in sport?

By Um-E-Aymen Babar

For Paralympian Monique Murphy the pain of endometriosis was worse than losing her leg.

For Wales rugby international Ffion Lewis it almost left her infertile.

And sports presenter Anita Nneka Jones was forced to freeze her eggs.

Endometriosis an incurable condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows in other parts of the body.

It affects one in 10 women.

A study by the charity Endometriosis UK found waiting times for the condition to be officially diagnosed have significantly deteriorated since the pandemic, increasing to an average of eight years and 10 months - up 10 months since 2020.

So, why does it take so long? How does it affect women in sport? And are things changing?

Sky Sports spoke to Murphy, Lewis and Jones about how the condition impacts them and what more can be done.

‘My experience of endometriosis has been worse than losing my leg’

In 2014, Monique Murphy fell from a fifth-floor balcony during a university party after a suspected spiked drink.

She suffered multiple horrific injuries and her right leg was amputated below the knee but it was the experience of her endometriosis that was more painful.

“After my accident I remember requesting an internal ultrasound because I was convinced something else was wrong,” Murphy told Sky Sports.

“Looking back, I can see the red flags but I thought having painful periods was normal.

“My mum and I would go to the pharmacy to get something stronger than Panadol but that should have been a doctor's appointment.”

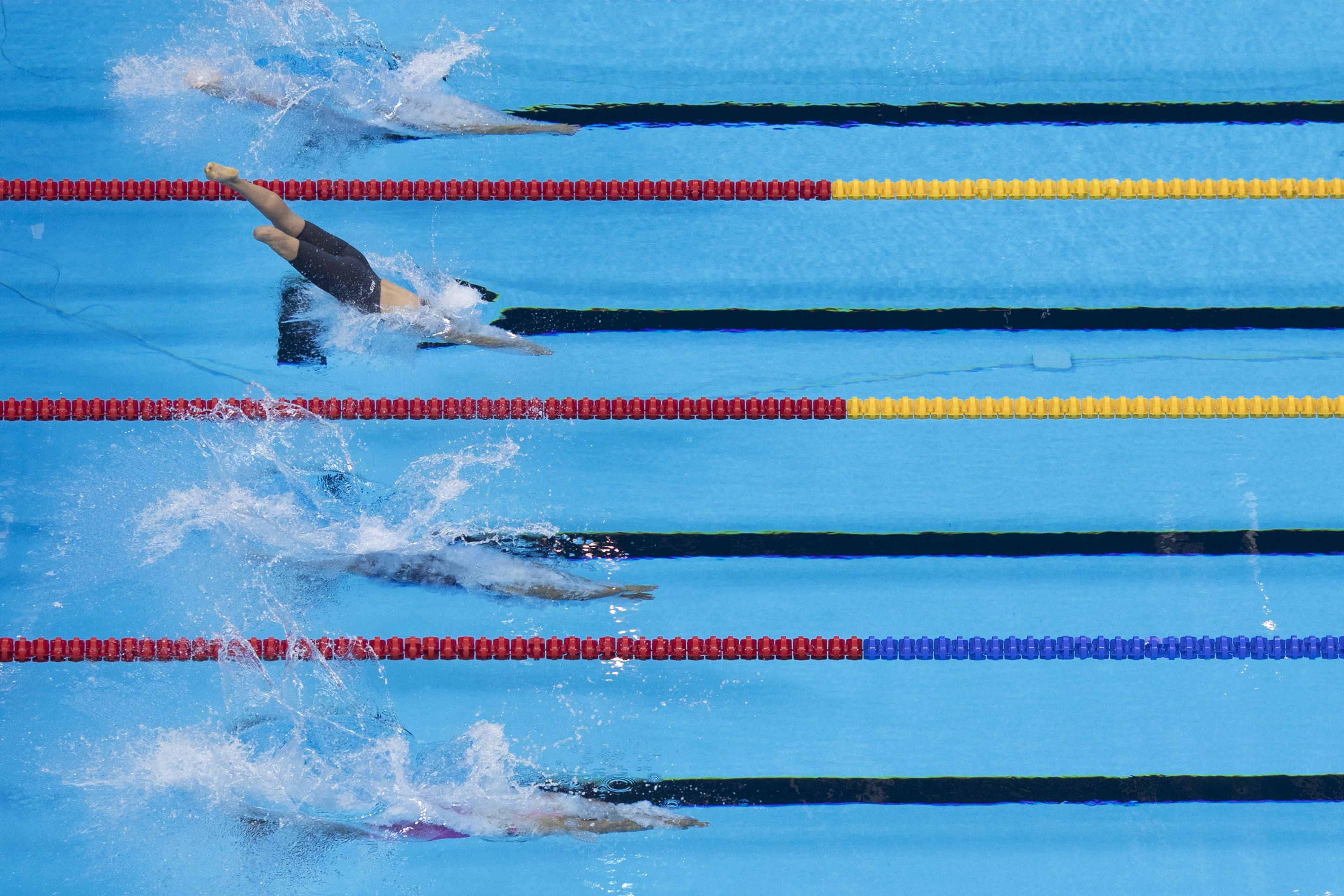

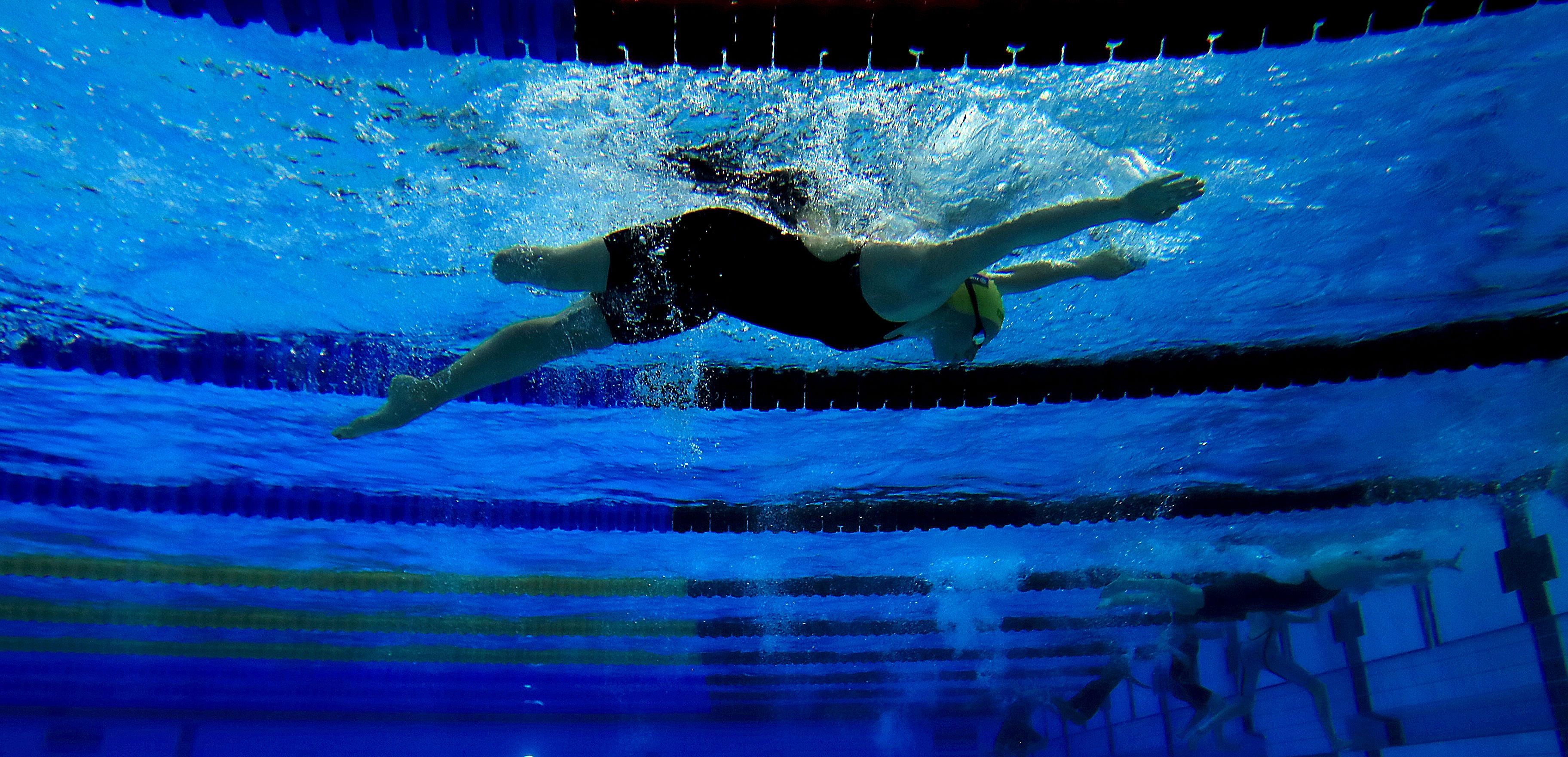

During the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games, Monique won a silver medal in the women’s 400m freestyle S10 exactly 900 days after her fall.

The world watched Murphy revel in glory but what they didn’t see was the pain she was suffering.

After her accident Murphy didn’t have a period for two years but it came back just before Rio.

“Usually my period is three days but I bled for two weeks,” Murphy said.

“I remember trying to talk to the team doctor because I was so stressed and all she said was: 'It’s a great thing your body is recovering from the trauma.'

“That’s how short the conversation was, she didn’t even look me in the eye.

“By the time I got to Rio I got sick. I had stopped bleeding a week before the race but I was feeling miserable. I raced well but it would have been nice not to be sick.

“In the following year, I had four periods and they really knocked me down. I thought I had gastroenteritis.

“I had a new coach and he said: 'Are you even a swimmer? How can you not make these time cycles?'

“I told the doctor I thought I had gastroenteritis and I got my period the next day. He laughed at me and said: 'Do you really think they’re related? They’re not related.' I didn’t bring it up again.”

‘I thought I wasn’t a good athlete’

Murphy had to go through 14 doctors until she received her endometriosis diagnosis.

“I’ve had surgery every year since my accident. We would notify the team, the physiotherapists would get involved and it was very hands on,” Murphy said.

“But when I got diagnosed, there was nothing. It was this foreign concept of women’s health and I was on my own.

“It was isolating because I was trying to learn about the condition myself, I didn’t have the capacity to teach other people too.

“When I came out of the surgery and they told me I had endometriosis, I cried.

“I started to think I wasn’t good as an athlete or I wasn't mentally strong. Those questions on your self-worth really tear you apart.”

Last year, Murphy made the difficult decision to have a hysterectomy after finding her endometriosis had spread.

“I did want to have kids so giving that up was incredibly difficult and unfortunately it’s still an ongoing investigation because it looks like the endometriosis is growing in my chest now,” Murphy said.

“I look at it as a delayed injury from the accident because if I only had endometriosis then it would be a different story.

“Because I’ve had so many surgeries and recovery is so long, my body is experiencing whiplash and ending up in severe pain.

“You want athletes to be predictable and just because another athlete needs a few extra steps that shouldn’t mean they get left behind.

“It would be easy to blame my body but I’m aware I put myself through a lot.

“I’m at the point where I’ll be retiring because my body is done, not because I want to.

“It’s upsetting but the blame doesn’t come on to me, it’s the medical community and how my sport manages these issues.

“I can’t change anything that’s happened to me. If I got diagnosed earlier, I could be sitting here with a uterus, who knows?

“But my accident taught me it’s really dangerous to think like that. I don’t have a right leg and that’s not coming back.

“There are more important things than a swimming career. Being an athlete is a privilege, it’s expensive and there are so many people who don’t get the opportunity to do it.

“You have to be aware that the blame doesn’t come back on you and your body.

“Change can be as little as someone seeing this and thinking they need to go to their doctor and that’s a positive.”

‘The choice to have kids shouldn’t be taken away’

Last summer, Wales scrum-half Ffion Lewis revealed her endometriosis was so severe it almost left her infertile.

Lewis shared on social media that her surgeon told her she was "riddled with endometriosis" and her chances of conceiving a baby "were literally single figures".

“I hadn’t even heard of endometriosis before my diagnosis and I didn't have a clue of what it was,” Lewis said.

“I still don’t know enough about it and I’m still learning.

“I’m not thinking about having kids any time soon but every woman should deserve to have a choice.

“It wasn’t until after my surgery I learnt about the severity of it and then it hit me.

“I was in a fortunate position where they were able to restore my fertility for the next few years but some people aren’t as fortunate.”

Lewis credits Wales team medic Jo Perkins for helping her get a diagnosis.

“I thought it was normal for a woman to have painful periods but Jo would raise things with me that I hadn’t noticed before,” Lewis said.

“In the mornings we would monitor how we were feeling and I would always flag that I hadn't slept because of my period pains.

“It was because of the knowledge in the club that I became aware that something was wrong.”

The decision to speak out after her diagnosis was much harder though.

“I sat on my Instagram post for over an hour thinking if it was really something I wanted to do.

“As soon as I shared it, the response was crazy. I had hundreds of messages from mothers that their daughters were going through it, from older women who had been going through it for decades, I had kids message me about severe period pains and I even had dads message me about it.

“It was really scary to be vulnerable but then I realised how many people it can affect and me speaking out helped so many people.

“I’ve had six people go to the surgeon I recommended and they have found endometriosis, that’s just from me speaking out so it shows how powerful it can be.”

A lengthy waiting period in diagnosis and accessing treatment means the disease may progress leading to worsening physical symptoms and a risk of permanent organ damage.

Research has found that risk of injury in women may be increased during the ovulatory phase of their menstrual cycle.

Lewis suffered an anterior cruciate ligament injury during the 2023 Women's Six Nations before her endometriosis surgery and the biggest lesson she has learnt during her road to recovery is the power in vulnerability.

“Speaking is so important and powerful. I wanted to break the stigma of women’s health,” Lewis said.

“Knowledge is power. You can’t be mad at people for not knowing, it’s about society being open to learning.

“I'm not worried about saying I'm having a bad day anymore, speaking out has given me confidence.

“I’m in a fortunate position because I found out about my diagnosis pretty quickly compared to other women so whatever knowledge I’m gaining I want to be able to share it.”

Not only does Lewis have to consider her rugby career when she has kids but also how advanced her endometriosis will be.

“Removing the growth has given me a three to five-year fertility window but unfortunately as an athlete my career comes first,” Lewis said.

“I want to make sure that I’ve maximised myself for my rugby career before I think about having kids.

“I don’t want to be in a position where I have to retire because I have a small window to have a baby, I want to make those decisions on my own terms.

“Sometimes I wonder, 'what if I didn’t share that post?' Those people messaging me might not have had surgery or been seen.

“It’s quite overwhelming and that just comes from one person speaking out about it.

“Being vulnerable is scary but that is the point. You could change someone’s life by speaking out.”

‘I decided to freeze my eggs’

Sports presenter Anita Nneka Jones remembers getting painful periods since she was 14 years old.

A year later she was hospitalised when doctors thought she had appendicitis, a common misdiagnosis.

At 18 the doctors put her on the pill but the excruciating pains still returned a few years later.

Jones was continuously told by doctors that her pain was normal until one day she saw a Facebook post about endometriosis and related to all the symptoms.

“I told the GP I wanted to see a gynaecologist and we did a scan but nothing came up,” Jones said.

“They offered to do a laparoscopy which is how most people are diagnosed.

“I decided to do it and they found endometriosis near my pelvic bone and abdominal wall so it was a very validating experience.

“My body had been giving me signs all these years that something wasn’t right but because I was told by people who were supposed to know more than me that I was fine, I believed them.

“I don’t know to what extent medical professionals have prejudices of what pain looks like in certain people but I’m aware that when it comes to giving birth, Black women are not taken seriously. That’s what pushes me to talk about it.”

Endometriosis is still under-researched and it remains difficult to understand what role race plays with a diagnosis.

These questions were put forward to Dr Shaheen Khazali, a gynaecologist and endometriosis specialist at HCA The Lister Hospital, who agreed that because periods remain a taboo topic in Black and Asian communities, it could mean these communities are under-diagnosed.

“I’m not aware of this being properly studied but these are very logical and reasonable assumptions,” Dr. Khazali said.

“In some cultures you don’t even want to talk to your mother about your periods. I practised in Iran for a number of years and I can tell you that there is certainly an element of that.

“It also means only the very advanced cases are dealt with where it would otherwise be impossible to live your life.

“You almost have as many women with endometriosis as you have women with diabetes, that’s how common it is.”

Despite having a laparoscopy, Jones continued to have complications with her period pains.

“I started violently bleeding at work one day and I couldn’t put my finger on it,” Jones remembered.

“I was worried my coil had moved but the scans showed it hadn’t. I spoke to a doctor who suggested I go see a fertility specialist because so many women who have a second surgery their egg reserves are depleted from it.

“I got checked and that’s exactly what they told me. My priorities completely changed.

“While some people were saving up for a mortgage, I started thinking about saving money to freeze my eggs.”

According to Endometriosis UK, 78 per cent of people who later went on to receive a diagnosis of endometriosis had experienced one or more doctors telling them they were making a 'fuss about nothing' or similar comments. The number of people reporting this experience has increased from 69 per cent in our 2020 survey.

"If you are suffering from painful periods., you need to seek advice from someone who knows about endometriosis," explained Dr. Khazali.

"If the pain is affecting you, it's not normal. It's important to listen to your body and find someone you trust."