Uruguay once led the way in football but the legacy of that success goes on at the 2022 World Cup – how does this country of just three million people still compete? With help from Martin Da Cruz, Adam Bate looks at how a proud history continues to inspire...

Thursday 24 November 2022 06:30, UK

Perhaps you have seen the video revealing the Uruguay squad for the 2022 World Cup. It has over eight million views. Not bad for a country of three-and-a-half million people. But then Uruguay has long had an outsized impact on this sport.

The video shows coach Diego Alonso with a map of the country, illustrating that Uruguay draws on the different regions to supply the national team. Darwin Nunez was born in Artigas, near the Brazilian border. Luis Suarez and Edinson Cavani are from Salto.

Each name is unveiled by a member of the public, from the gauchos on horseback and the farmers in the fields, to the fruit sellers, factory workers and bus drivers in the capital of Montevideo. That sense of unity through football is the story of Uruguay as a nation.

"Uruguay has always had much more than football," Martin Da Cruz tells Sky Sports. "It has had some of the most progressive social policies in the region and the world. It is a leader in the use of renewable energy. But football still plays a huge role.

"Players like Fede Valverde and Darwin Nunez are perhaps the most powerful ambassadors for the country. Football seems to cut through the most. The national team is perhaps the only thing that can unite all Uruguayans, no matter where they lean politically."

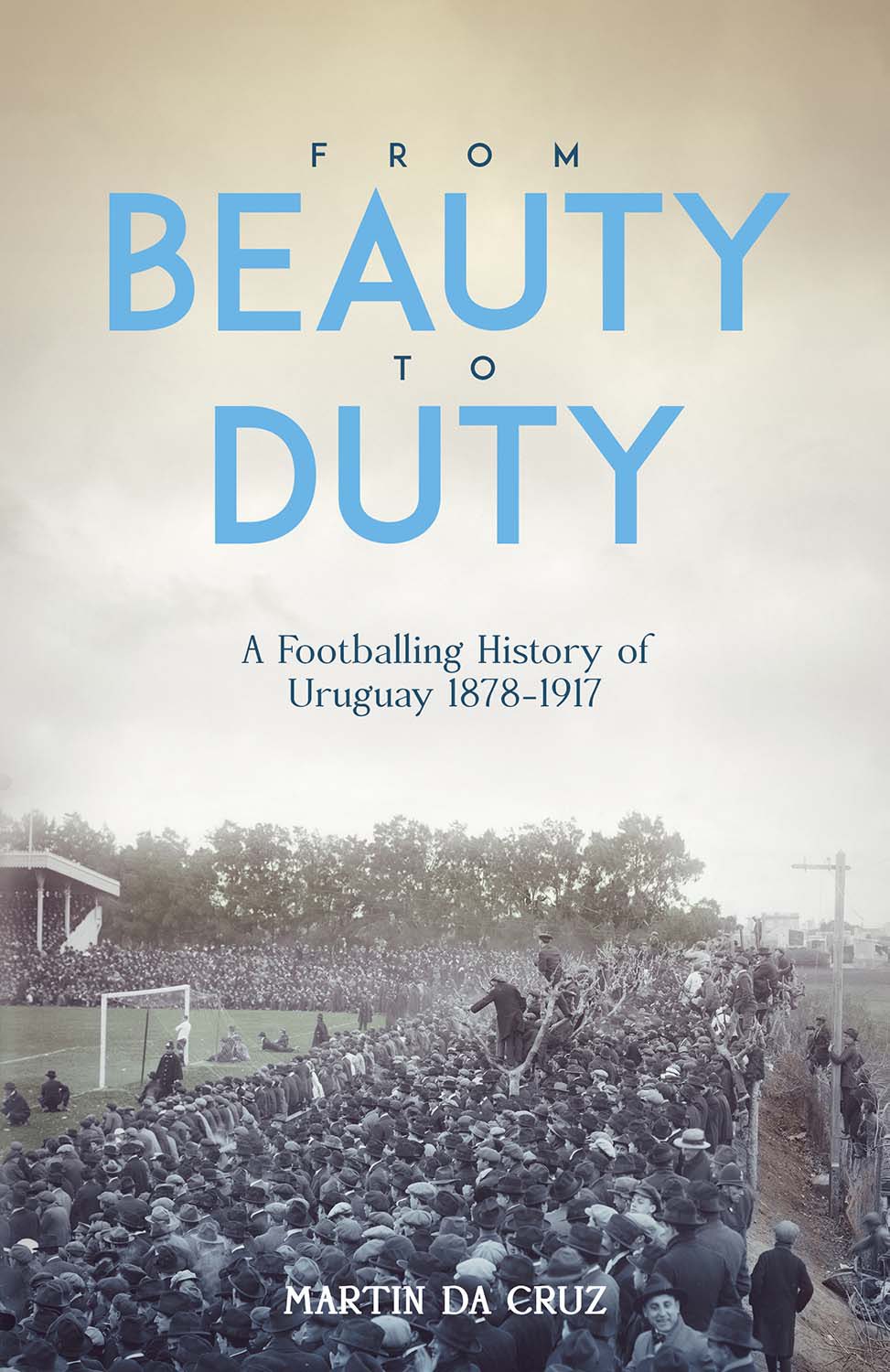

Da Cruz has written a book, From Beauty to Duty, that helps to explain football's role in nation-building in Uruguay. It details the game's rise in popularity in the 19th and early 20th centuries, at a time when the long-term existence of the fledgling Uruguay was no fait accompli.

"A precarious existence between two imposing giant neighbours Brazil and Argentina has always been a key feature of Uruguay's national narrative and is still relevant to the country's self-perception. This has touched football since the beginning.

"Uruguay used the game to prove its right to exist."

As neighbours grew and naval ships from the old world patrolled La Plata, Uruguay found its identity through football. During civil war, its growth was accelerated as the government-owned newspapers could not write of revolution. Football filled the void.

The game thrived, embraced by willing amateurs and eventually the populace at large. Olympic success stoked national pride. World Cup glory ensured that those achievement would echo through the ages, defining Uruguay, past, present and future.

As the football writer and poet Eduardo Galeano once put it, 'Every time the national team plays, no matter against whom, the country holds its breath. Politicians, singers, and street vendors shut their mouths, lovers suspend their caresses, and flies stop flying'.

Uruguay's status as a footballing super-power - they are still one of only eight countries to have won the men's World Cup and they have won it twice - is so embedded in the game's history that is easy to forget just how outrageous that accomplishment remains.

The other seven nations to win the tournament have populations in excess of 45 million. When Uruguay face South Korea, Ghana and Portugal in Group H they will be perceived as heavyweights expected to progress despite being a fraction of the size.

Uruguay are football's ongoing miracle.

"It is an amazing football story, but it should not come as a surprise," says Da Cruz. "Though small, Uruguay was the first South American country to really entrench football into its national customs and produce a 'proper' football culture.

"So, those early international victories, the first South American and world championships left a huge legacy that has endured generation after generation, with young Uruguayans always looking back at something to emulate, something to aspire to."

Just as this most recent video celebrates the different creeds and cultures among the Uruguay squad, that diversity has been a feature from the start. Jose Leandro Andrade, nicknamed 'The Black Marvel', was instrumental in Uruguay's 1930 World Cup win.

Even he was standing on the shoulders of giants. Juan Delgado and Isabelino Gradin were the first Black players to be fielded in an international football tournament - winning the 1916 South American championship for Uruguay. Gradin was the top scorer.

"They were the real trailblazers," says Da Cruz. "Uruguay's early democratisation, the early and constant inclusion of footballers of all backgrounds was a massive part of their success," he adds.

"It also fit perfectly into the early national narrative of Uruguay aspiring to become what former president José Batlle y Ordóñez coined as a small model country, a melting pot, an egalitarian society where merit not background determined your success.

"Of course there are complexities to that pleasant narrative of social inclusion equalling footballing success. Black players were included in Uruguay's national story as an equal and homogenous society, but their blackness was officially ignored.

"Delgado and Gradin triumphed but they still suffered injustices in football due to the colour of their skin, which also reflected everyday life. And today, Uruguayan football still has its own racism problems with crowd incidents occurring almost every year."

That is the challenge for Uruguay now, a country that knows it needs to look forward but one that has had to come to terms with the idea that the glories of the past are gone. It is a numbers game. As football becomes more popular globally, it gets harder to compete.

The future can be a scary place. The past is a comfort but it is a long time ago now - and that is obvious on the streets of the capital. The monuments in Montevideo, much like the British cemetery to the east of the city, can appear as if they belong to another age.

The crumbling Estadio Centenario, host of the first World Cup final and declared by FIFA as a historical monument, perhaps the true home of football, now bears closer resemblance to the Colosseum of Ancient Rome than the modern stadia of Europe.

The commemorative statue outside it bears the inscription of past World Cup winners but stopped adding new names late in the last century. The site of the first World Cup goal is now a bus stop in a quiet residential street. The museum is a dusty treasure trove.

Uruguay honours its past but seems unsure how much to shout about it. "It is mainly administrative incompetence and the concentration of wealth in vested interests that has ensured that Uruguay has not fully celebrated its past as it should," says Da Cruz.

"But there is a very fine balance between being proud and not to be seen as obsessing with the past. Uruguayans should be very proud but history can give you only so much, so behind this huge pride is also a humbleness, an acceptance that the world has caught up."

That proved to be the case last summer when neighbours Argentina levelled Uruguay's record total of Copa America wins. It is 34 years since a Uruguayan club won the Copa Libertadores. "Sadly, it's hard to see a future where one wins it," says Da Cruz.

"Uruguayan football has big problems domestically. A lack of money and infrastructure has ensured that clubs from Brazil have left Uruguayan clubs behind. Any young talent leaves the country before they have barely featured for the first team."

But amid the laments to what is lost, there remains hope.

The cycle continues.

Just as Diego Forlan made his professional debut in the same season that the great Enzo Francescoli departed the stage, Suarez and Cavani look likely to make their exits just as Nunez begins to establish himself as one of the best strikers on the planet.

Inter youngster Martin Satriano scored his first Serie A goal out on loan in September. Teenager Alvaro Rodriguez is showing promise at Real Madrid. "We can be optimistic if we look at talent production," says Da Cruz. "Uruguayans continue to triumph in Europe."

And so, Uruguay's football miracle goes on.