Manchester United's five years of failure examined: How and why the trophies stopped and key factors explored

With five years now having passed since Manchester United's last trophy, we look at how and why it went wrong for a club that had once been synonymous with success...

Tuesday 31 May 2022 10:46, UK

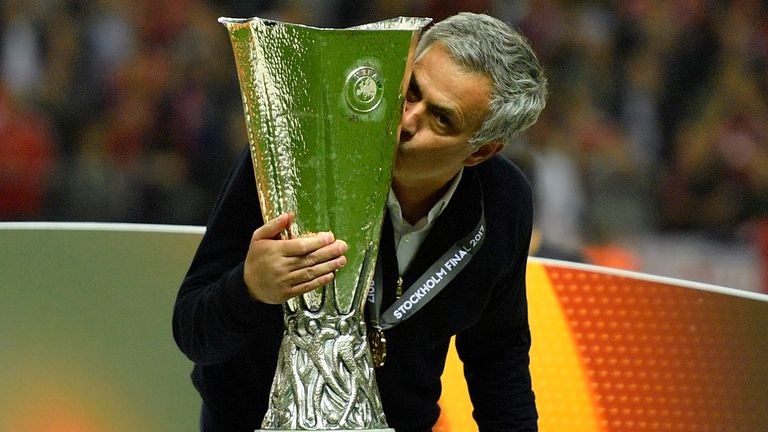

"The last piece of the puzzle." That is how Jose Mourinho described Manchester United's Europa League final win over Ajax in May 2017. United were, he pointed out, now a club that had won every trophy in the world of football.

The victory that night in Stockholm was supposed to be the beginning, not the end. It may have been their third trophy of the season - as Mourinho memorably gesticulated with his fingers - but it had also been what he described as his most difficult season as a manager.

United muddled through at times, finishing sixth in the Premier League. But back then even a spluttering version of the red machine seemed capable of churning out silverware. Louis van Gaal had been sacked with the FA Cup plonked right in front of him.

There was an acceptance that United needed to improve and an assumption that they would. Instead, the fifth anniversary of that win came and went but it remains the club's most recent trophy. Liverpool have won six since then. Manchester City have won 11.

How has that happened? How has it been allowed to happen? It is a tale of hubris and self-harm, a club hindered by too many voices and too few. From ownership to recruitment, the problems were myriad. The solution? It is unclear whether that has yet been found.

- Ten Hag on Ronaldo, Maguire and breaking Pep-Klopp dominance

- Man Utd's summer transfer plans analysed

- Transfer Centre LIVE! | Man Utd transfer rumours

- Get Sky Sports | Download the Sky Sports app

Nobody knew that yet in Sweden. United had been Premier League champions just four years earlier and here they were winning a European trophy. For all the fuss with David Moyes, the struggles of Van Gaal, the doldrums might yet be navigated relatively swiftly.

As soon as the trophy had been won, and with it Champions League football for the following season secured, thoughts turned to the future. Albeit one that would be determined by the recruitment of the executive vice-chairman rather than Mourinho.

"Ed Woodward has had my list, what I want, what I would like, for more than two months," said Mourinho. "So, now it's up to him and the owners. I wish Mr Woodward all the success in his work because now it's time for me to disconnect, because I'm very tired.

"I am going to land in Manchester, I am going to get a car to London, then to Portugal. I don't care about football for now. Now I am on holiday. I don't want to see any international friendlies. I am selfish. I can't do it. For me, enough is enough."

It was a punchy statement in the aftermath of victory that hinted at the unrest behind the scenes that was already developing less than a year into the job. The pointed remark that Woodward had been aware of his demands for months implied a lack of progress.

Mourinho wanted to sign four players that summer. In the end, United delivered three. Victor Lindelof was signed from Benfica. Romelu Lukaku arrived after scoring 25 Premier League goals for Everton in the previous season. Nemanja Matic came from Chelsea.

"I cannot say that I am happy," said Mourinho. "What I can also say is that it is a difficult transfer window and I don't blame anyone - it is just a reality of things. The market is going in such a direction that many players are difficult to get, not to say impossible."

It was still a transfer commitment in excess of £150m, but history has not treated those decisions kindly. They did not occur in a vacuum. Others did not find it so impossible. Even as United were trying to close the gap on their rivals, their rivals were widening it.

Manchester City had struggled to play the football that Pep Guardiola wanted in his first season in charge, in part because of their ageing full-backs. That was addressed emphatically as huge sums were spent to bring in three of them, including Kyle Walker.

Just as significantly, City signed Ederson as their new goalkeeper and brought in Bernardo Silva. They would go on to finish as Premier League champions that season with a record 100 points, but were eliminated from the Champions League by a resurgent Liverpool.

Jurgen Klopp's side had been busy too. They signed Mohamed Salah in June 2017 from Roma for an initial £36.5m, a player Mourinho had bought and sold during his time at Chelsea after allowing him only half a dozen Premier League starts for the club.

Liverpool also pursued Virgil van Dijk, a transfer they finally completed in January. According to Charlie Austin, Van Dijk's Southampton team-mate, the Dutchman had been a target for United. He told Austin: "It was between me and Lindelof, and they signed Lindelof."

Van Dijk's signing had a transformative effect on Liverpool, although some queried the £75m fee. United's own winter business was considered by many to be the shrewder work as Arsenal's star player Alexis Sanchez arrived in a swap deal for Henrikh Mkhitaryan.

It meant that in January 2018, Manchester United had two of the three highest scorers from the previous Premier League season. On the face of it, Sanchez was the missing fourth signing that Mourinho had wanted when missing out on Ivan Perisic in the summer.

But Sanchez proved a spectacular failure from the outset, scoring only twice in 12 Premier League appearances that season, in home wins over Huddersfield and Swansea. The following season he scored twice as many goals for Chile as he did for United.

Mourinho would go on to describe the achievement of finishing second in that 2017/18 season as among his best. But the failure to win a trophy, coupled with these disappointments in the transfer market, began to erode trust.

Lindelof and Eric Bailly had been brought in but the search for a centre-back continued with the price for Harry Maguire jacked up because of Liverpool's deal for Van Dijk. Other targets such as Toby Alderweireld and Jerome Boateng were seen as the wrong age profile.

The result was that the only signings in the summer of 2018 were Fred and Diogo Dalot. The complaints of the coach became an underlying theme as results suffered and relationships deteriorated. Any sense of momentum had been lost. Mourinho was sacked.

Ole Gunnar Solskjaer's appointment as a caretaker manager was genuinely inspired. The team played with freedom again, a club refreshed. The fan favourite won his first eight games in charge. But his surprise success was the prelude to the next big mistake.

Solskjaer lost only one of his first 17 games - and that was a first-leg defeat to Paris Saint-Germain that was turned around in dramatic fashion in the French capital. That evening, Rio Ferdinand spoke for many supporters when urging for him to be given a long-term deal.

This brief success offered renewed belief that the club's much-maligned structure was not the issue and nor was the recruitment. The problems had been solved by identifying the right man to lead them. He understood the club and the clouds had been lifted.

The deal was signed later that month but United had been knocked out of the FA Cup by then and their Champions League exit followed. They won one of their last nine games. Mourinho had been dismissed in December with United sixth, which is exactly where they finished.

The bounce over, a lack of substance and strategy started to become a concern. Solskjaer had brought some unity in difficult circumstances but time on the training ground and a summer in which he was backed in the transfer market would test different skills.

Maguire became the most expensive defender in transfer history. Aaron Wan-Bissaka was brought in for £45m amid talk of a database of over 800 right-backs being forensically analysed to arrive at the optimum signing. City signed Joao Cancelo and Rodri.

Solskjaer finishing third in his first of his two full seasons in charge and second in the next is no great slight on his performance given the quality of the title-winning teams. He was able to engineer some fine tactical wins in big games with a counter-attacking approach.

But that lightness of his touch, the absence of any over-arching idea regarding a playing philosophy, meant that there was never really any hint that United were about to usurp their rivals. And no trophy to galvanise the group, giving them that hunger for more.

There were three semi-finals in the 2019/20 season, all of them lost. The defeat to Manchester City over two legs in the Carabao Cup was explicable but David de Gea's two errors at Wembley ended their FA Cup hopes and Sevilla did for them in Europe.

The following season, Solskjaer lost his third quarter-final and his fourth semi-final but did go all the way in the Europa League. Warm favourites to beat Villarreal, instead they lost in a drawn-out penalty shootout, De Gea again enduring a tough night, missing the vital kick.

"You can't switch performances on and off like a tap," said Gary Neville. "Pressure will be applied to Ole and the team. Rightly so. Need to get it right this summer and a good start to next season needed badly." More signings were made but United did neither.

The arrivals of Raphael Varane, Jadon Sancho and Cristiano Ronaldo should have elevated United. Instead, they fell away. It was a huge outlay but another critical failure, signings that seemed to suit differing styles of play, and a coach with little plan on how to deploy them.

A 5-0 home defeat to Liverpool could have cost Solskjaer his job, the 2-0 strangling by Manchester City back at Old Trafford the following month should have done. Ultimately, it was a 4-1 capitulation at Watford that brought it to an end with United down in seventh.

If Mourinho had been appointed a decade too late, Solskjaer had perhaps stayed on two years longer than was sensible. But a November sacking - straight after the final international break of the year - was indicative of the ongoing poor planning at the club.

Antonio Conte had taken the Tottenham job just weeks earlier. Now, United found themselves searching for a new coach in a market where the best were unavailable. The decision to turn to Ralf Rangnick, sporting director at Lokomotiv Moscow, proved it.

Talk of a consultancy role beyond the end of the season looked like obfuscation. This was an interim manager brought in to see things through until the summer with a remit to secure Champions League qualification and perhaps end that wait for a trophy.

Again, they achieved neither. Eliminated from the FA Cup by Middlesbrough, they dipped out of the top four having failed to win at home to Watford. Rangnick would later bemoan the lack of investment in January but his position was awkward from the outset.

Was he here to solve the problems or merely diagnose them? His much-vaunted consultancy role, which has since been abandoned, was undermined by the frequent admission that he had yet to consult with Erik ten Hag even after the Dutchman had been announced as the next boss.

The feeling throughout was of another wasted season. Five of them now. Lurching from Mourinho to Solskjaer. The rendezvous with Rangnick. And now Ten Hag, the man Ajax appointed in 2017. The last piece of the puzzle? United have been here before.

- What must Ten Hag solve at Man Utd

- McClaren confirmed as Man Utd assistant to Ten Hag

- Brighton 4-0 Man Utd - Match report and highlights

What are the issues behind the scenes?

Ownership

Since becoming majority owners of Manchester United in 2005, the Glazers have faced relentless fan anger and backlash. The reason why is quite clear - debt.

Purchasing the club through loans totalling £525m, the Americans then leveraged this debt onto the brand of Manchester United. Debt-free until their takeover, United were in the red by £495m at the end of 2021. In total, the Glazers have also taken more than £1bn in interests, costs, fees and dividends out of the club.

Supporter protests have been a recurring theme throughout the Glazers' 17-year ownership, none more so than when last year's Premier League fixture against Liverpool was postponed after hundreds broke into Old Trafford and demonstrated on the pitch.

That followed the failed European Super League proposals - backed by the Glazers - while more protests have taken place this season.

Despite the anger aimed at the family, though, United have continued to spend large amounts of money on incoming transfers - £1.3bn in the past 10 years, according to a study by CIES Football Observatory.

And in a short conversation with Sky News this week, co-owner Avram Glazer vowed to fund new manager Erik ten Hag's summer spending.

When asked about offering financial support to the Dutchman ahead of next season, Glazer said: "We've always spent the money necessary to buy new players."

Hierarchy

As well as the Glazers, the lack of clear structure within the club's hierarchy has also baffled and irritated Manchester United fans over the past decade.

Until recently, the absence of a director of football had often been questioned as clubs domestically and around Europe modernised behind the scenes. Only last year did United appoint John Murtough as the club's first football director and Darren Fletcher as technical director. Andy O'Boyle has since been named Murtough's deputy, which suggests a step in the right direction, but there remains some scepticism over what will change.

Richard Arnold is now in charge of running the club, but most of that lingering uncertainty stems from the man he has succeeded - Ed Woodward.

Woodward, who left the club in February, helped facilitate the Glazers' takeover in 2005 and succeeded David Gill as executive vice-chairman in May 2013. An accountant and investment banker, the 50-year-old was responsible for hiring and firing several managers and overseeing over £1bn on incoming transfers.

Since Woodward's departure, Erik ten Hag has officially been named United's next manager. That may yet prove to be a masterstroke, but Ralf Rangnick has not held back on publicly suggesting where the club has gone wrong in recent years.

"In Germany, we have a head coach and then there is usually a minimum of two skilled people continuously in the club on a longer-term basis responsible for recruitment, scouting and any daily operation," Rangnick told Sky Sports News in April.

"They also bring in the right and best possible head coach for the team. This still hasn't got a big tradition here and so the job of a sporting director or director of football - only a few clubs have that.

"I know that for the future, and I think even more so for a big club like Manchester United, you can't put all those jobs and tasks and the whole responsibility only on the shoulder of one person - on the manager. I'm not sure if this can be dealt with by one person, no matter how good he is."

Stadium and facilities

"You look at the club now, this stadium I know it looks great here [on TV] but if you go behind the scenes it's rusty and rotting," Sky Sports pundit and former Manchester United captain Gary Neville said in 2020.

Old Trafford has not been redeveloped since 2006 and only last month did the club announce the appointment of leading consultants to work on redevelopment plans.

The Glazers have been criticised for neglecting the club's facilities while their domestic rivals - including Manchester City and Liverpool - have modernised across the board or moved home.

"The training ground is probably not even top five in this country, they haven't got to a Champions League semi-final in [11] years and we haven't won a league here for [nine] years," Neville continued.

"The land around the ground is undeveloped, dormant and derelict, while every other club seems to be developing the facilities and the fan experiences.

"The Glazer family are struggling to meet the financial requirements, and the fans are saying enough is enough."

After the failed European Super League plot in April last year, co-owner Joel Glazer promised to upgrade Old Trafford. The work has at least now been organised, but a reactive rather than proactive approach is what continues to frustrate supporters.