Keith Treacy on the alcohol addiction that ended his career at 26 and wanting to help others avoid his mistakes

In an exclusive interview with Sky Sports, former Premier League player and Republic of Ireland international Keith Treacy reveals how alcohol addiction curtailed his career and why he hopes others will heed the lessons that he learned too late...

Thursday 22 July 2021 22:49, UK

It had been a slow descent but when the end finally came it was swift. Barnsley had wrapped up their training early that Christmas Day in 2014 to allow the players to enjoy Christmas dinner with their families. That was no good to Keith Treacy.

All on his own, dinner was a bowl of pasta. Dessert was a bottle of vodka and a bottle of whisky. "They were both gone in the morning," he tells Sky Sports. Alarming in any circumstances but particularly when Treacy was due to play at Preston on Boxing Day.

"I woke up with the door being knocked by the driver who was going to take me to the game. There was blood and sick all over my sitting room where I had passed out. There was just that much harsh alcohol going into my system that I was vomiting blood.

"He actually wanted to ring my mother and father because I was not in any fit state but I had a shower and sat on the bench at the game. I actually did the warm-up but as I turned to sprint, the people in the stands were getting blacker and blacker.

"My peripheral vision was coming in and in. It was like tunnel vision. I told the gaffer that I had flu and could not play. He told me to sit behind the dugout and stay away from the lads.

"I jumped on a plane to Dublin and I never went back."

Treacy had been a genuine talent, his direct running impressing manager Graeme Souness as soon as he arrived at Blackburn. He made his Premier League debut in 2008 while still a teenager in a win at Everton and before long he was a Republic of Ireland international.

But his professional career in England was over by the age of 26. He never returned to Barnsley or anywhere else, a career cut short by addiction. Only now, almost seven years on, is he beginning to rebuild, contemplating a return to football back home in Ireland.

Even that Christmas was not quite the end of his troubles. "I wouldn't say that was the penny dropping but it was definitely a bit of a turning point." Still, there were two more years of "alcohol, holidays, women and horses" before burning through his savings.

"I was not drinking because I liked the taste. I was drinking because I wanted to black out and forget, get up in the morning, get the football out of the way and do it all over again.

"Rock bottom was waking up in bed and all I could think about was going back to the pub. I think I was at the point where I could have lost my life with it. I was drinking to hurt myself."

Treacy is not seeking sympathy. "I made a lot of bad decisions," he says. "Nobody had a gun to my head and was forcing the drink down me or forcing me to do any of the other stuff I was doing. It was all me." But could more be done to anticipate the problems he faced?

He appreciates the support of the PFA but wonders whether it is reactive not proactive. He thinks of the managers who enabled him and a culture that placed extraordinary demands on a boy of 15 in a new country. The surprise is that more do not suffer the same fate.

"It was quite a culture shock so to have nobody trying to settle you in or relax you or give you something to do after 1pm when you finish training," adds Treacy.

"There is only one way you are going to go."

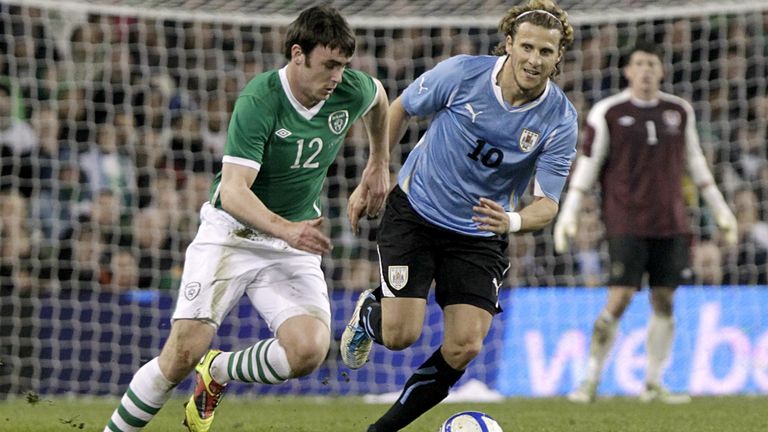

Part of the problem for Treacy is that his ambitions were achieved early. The goal of playing in the Premier League was ticked off in quick time. His international debut came under Giovanni Trapattoni at the opening of the new Aviva Stadium against Argentina.

The story of that night sums up Treacy's mentality. It should have been the start of something but it felt like the end. He walked out of the ground and made his way to the pub to see his grandfather just a stone's throw away, handing him his shirt from the game.

"I remember everyone calling me and saying, 'You played against Lionel Messi and Angel Di Maria.' I just wasn't interested. I just wanted to go. I walked out of the stadium, down to the pub, gave him the jersey because it was around his birthday, and we had a few pints. I could probably tell you more about the night in the pub than the match itself."

It is a tale that makes you wonder whether he was ever cut out for the professionalism of football at the highest level. "I was always bogged down with the idea, when I was playing in a big game, that I should not do anything wrong. Do not give the ball away," he says.

"The higher up you go the more that gets coached into you. Don't lose the ball, don't run with the ball. Pass and move, pass and move. I was a winger who liked to run with it so that sort of stuff gets knocked out of you. You start to lose what got you there in the first place.

"Did I ever enjoy it? Not really. I never came off the pitch thinking I had really enjoyed it. It is all tactical. Even now, when you watch a game of football, it is all tactics. We keep it for 10 minutes, you keep it for 10 minutes. Very few teams go for the jugular.

"I was asked not so long ago what my ambitions were. When I was a kid it was to play in the Premier League and play for my country. I did not put a goal of 100 caps on it. I was not very ambitious with my thinking. By the time I was 21 I had done it.

"The fire really did start to go out in me at that point. I just was not hungry any more. I was doing well financially and the drink took hold. I had reached the top of the mountain and everything hit me all at once. I started to get a bit heavier around the waist."

Such was his talent, it took time before decline set in. But the seeds were sown early. At Blackburn, he would see Roque Santa Cruz skipping sessions because of chronic injuries and others such as Robbie Fowler taking it a little easy. He looked for shortcuts himself.

"I thought I was on the same level, getting carried away and thinking I could do that too." Later on, after being moved on, his alcohol problems increased and it was affecting his game. "I played games drunk for Preston," he admits. "I played games drunk for Burnley."

One particular occasion stands out. It was a midweek cup tie for Burnley against Cardiff. Eddie Howe had hooked Treacy early on against Coventry at the weekend so there was no expectation that he would be selected. Then, he was summoned to the front of the bus.

"I remember while I was walking down there were comments from the lads that I stank of drink." Much to his surprise, Howe did not berate him but instead told him that he was starting the game. "It was the last thing that I wanted because I was drunk on the bus."

Predictably, Burnley lost. Unpredictably, Treacy came close to scoring. "The ball bounced, I saw about 42 footballs and just swung and hit one of them. I managed to get away with that one but it was only ever masking the problem, digging the hole deeper."

There are times when Treacy lapses into something approaching an after-dinner routine when telling the tales that you suspect have raised a laugh or two down the local.

Deep down, however, he knows there is a side to the stories that is anything but funny. He is convinced that the problems are still widespread in football but being hidden from view.

"When Paul Merson and Paul Gascoigne were playing, people were saying, 'They are too fit to be drinking these days.' Then, when I was playing, people were saying, 'They are too fit to be drinking these days.' They are still saying it, that lads are too fit to be drinking like I did.

"I guarantee that there are people struggling with it today."

The modern player must deal with the perils of social media, too. That is a challenge that Treacy readily admits caused problems for him even a decade ago.

"I would really go looking for those comments. It would only be a minority but it would affect me. I would be on the pitch with the ball at my feet thinking, 'Remember that guy who said you aren't great at running with the ball.' It just has a huge negative effect.

"The abuse that you get, I really do see very few positives in it. It is very rare that you will pick up the phone, read a couple of positive comments and then put it away feeling great about yourself. Everybody is trying to take you down."

It is part of the reason why he dispensed with his phone. Treacy is contactable now through his wife Leanne. "It is just me trying to take away temptation," he explains.

"If I had a phone I would probably soon be trying to meet up with someone for a drink or putting a bet on a horse so it is just better for my own peace of mind."

Thankfully, he has found some peace now.

"I am in a much better place mentally and physically," he adds.

"I had four years of therapy. It took a lot of pushing to get me in the therapist's room but I was walking out of there with 10 kilos taken off my shoulders every time."

He has been sober for almost four years and is even playing football again.

"I am in training and looking to come back, but it will be just to play for fun, keep me ticking over and getting back into a routine with my family.

"It just feels like the right time. Although my body has been through a lot, I am still only 32. I don't want to be disrespectful to the level in Ireland but I feel that I can still play here."

It helps to explain why he has thus far refused calls for him to write his autobiography. "I don't want to write my story yet because I feel like there is a way to go."

The journey has not always been a pleasant one. His addiction has cost him family and friends who "do not really want to talk" any more. The only player from his career in England who he is still in touch with is the former Scotland international Ross Wallace.

But he wants to reach out and help others.

"I have no agenda, I don't want to be plastered over social media and I don't want money. If I can help someone cope with the demands of the game, anything like that, I want to do it. If I can make a young player feel a little bit better about himself then my job will be done.

"Anyone who thinks that I might be someone who could relate to them, please do get in touch because I am not here to judge or to tell your manager. Maybe you will go on and do brilliantly with me having played a small part. That would make me feel great.

"I just wish the penny could have dropped for me sooner."