How Arsenal became woven into Black identity and culture

As Sky Sports celebrates Black History Month, the creator of a new book called Black Arsenal tells Nick Wright about Arsenal's unique connection with Black identity and the players who helped to shape it

In August 1992, on the eve of the inaugural Premier League season, Arsenal manager George Graham summoned his players to Highbury to acclimatise to the prospect of playing in front of a huge mural concealing construction work on the North Bank.

Noting the absence of any Black faces among the rows of supporters depicted in the mural, which had been commissioned by the club to an external design firm, a perplexed Kevin Campbell approached passing vice-chair David Dein with a question.

"Mr Dein," he said. "Where are my brothers?"

It proved a significant intervention.

Dein, embarrassed by the oversight, offered apologies to Campbell and his Black team-mates and promised swift action. By the time of Arsenal's second home game of the campaign, following a 4-2 loss to Norwich in their opener, the mural had been corrected to give a more accurate representation of the club's increasingly diverse fanbase.

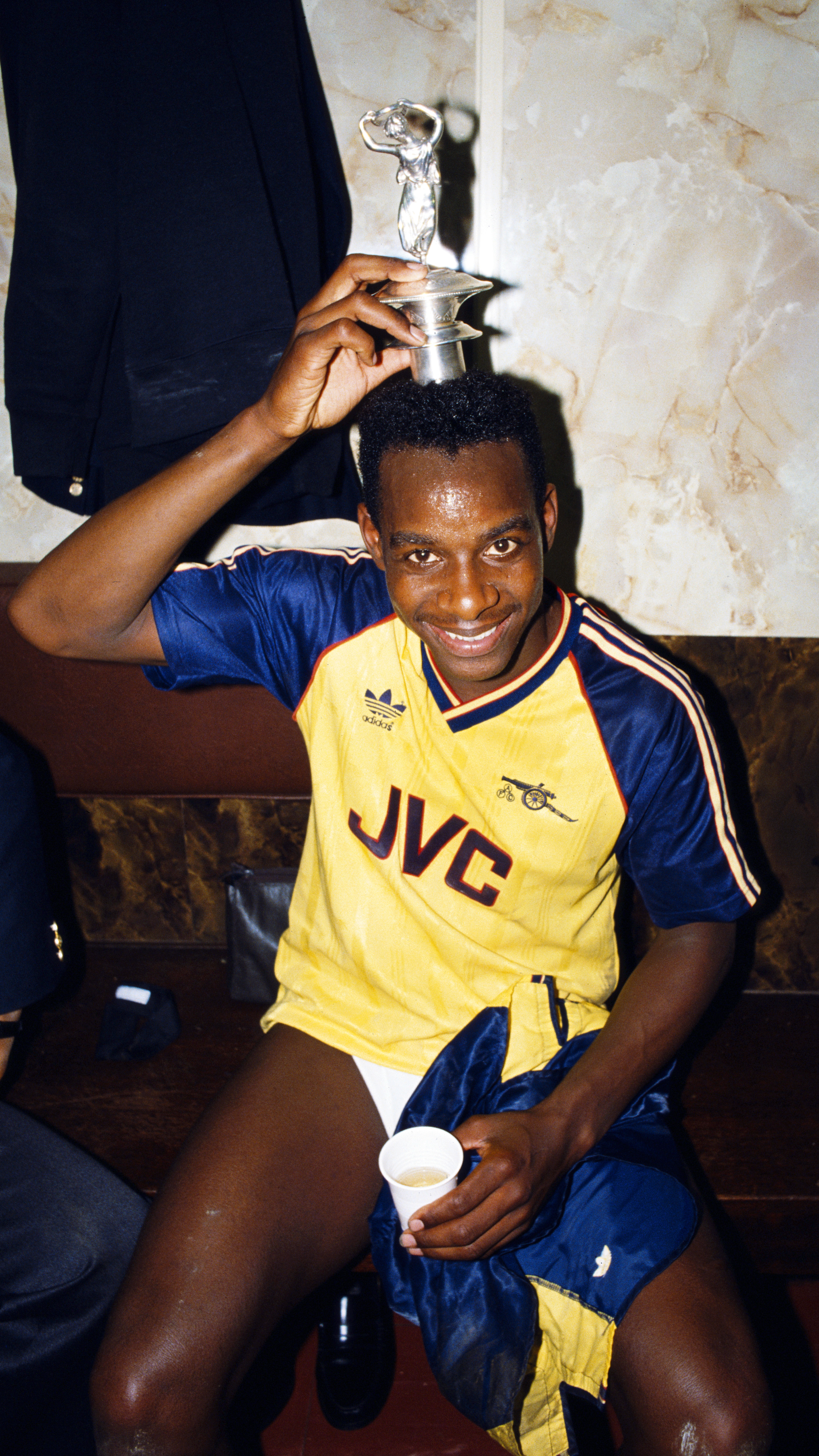

Campbell's approach to Dein was recounted by his former Arsenal team-mate Paul Davis during a tribute to the striker, who died aged 54 in June, at the launch of Black Arsenal, a new book exploring the club’s relationship with Black identity and culture. It is also the focus of a chapter of the book written by Amy Lawrence.

Kevin Campbell, who scored 59 goals in 228 games for Arsenal, died aged 54 in June

Kevin Campbell, who scored 59 goals in 228 games for Arsenal, died aged 54 in June

According to creator and co-editor Clive Chijioke Nwonka, it highlights the unique Black connection that inspired the project.

"I'm not convinced you could write a book like this about any other club in world football," Nwonka tells Sky Sports.

"Of course, a lot of clubs have had Black players. I've had comments saying, 'What about West Ham in the 60s? What about Luton Town?'

"And yes, you had Black players playing for those clubs. I don’t deny that. But how has that impacted or influenced the culture of the club beyond what is on the pitch?

"I think Arsenal is the only club where you can evidence its Black connection beyond singular players."

"Where are my brothers?"

- Kevin Campbell

Black Arsenal showcases that connection in illuminating style, outlining the club’s affinity with Black identity, rooted in post-war migration from the West Indies to north London, with the help of contributions from players, fans, journalists, academics and musicians.

"It is about how it influences society, culture, politics, fashion, music," adds Nwonka. "The book really tries to attend to those things as well as the players themselves."

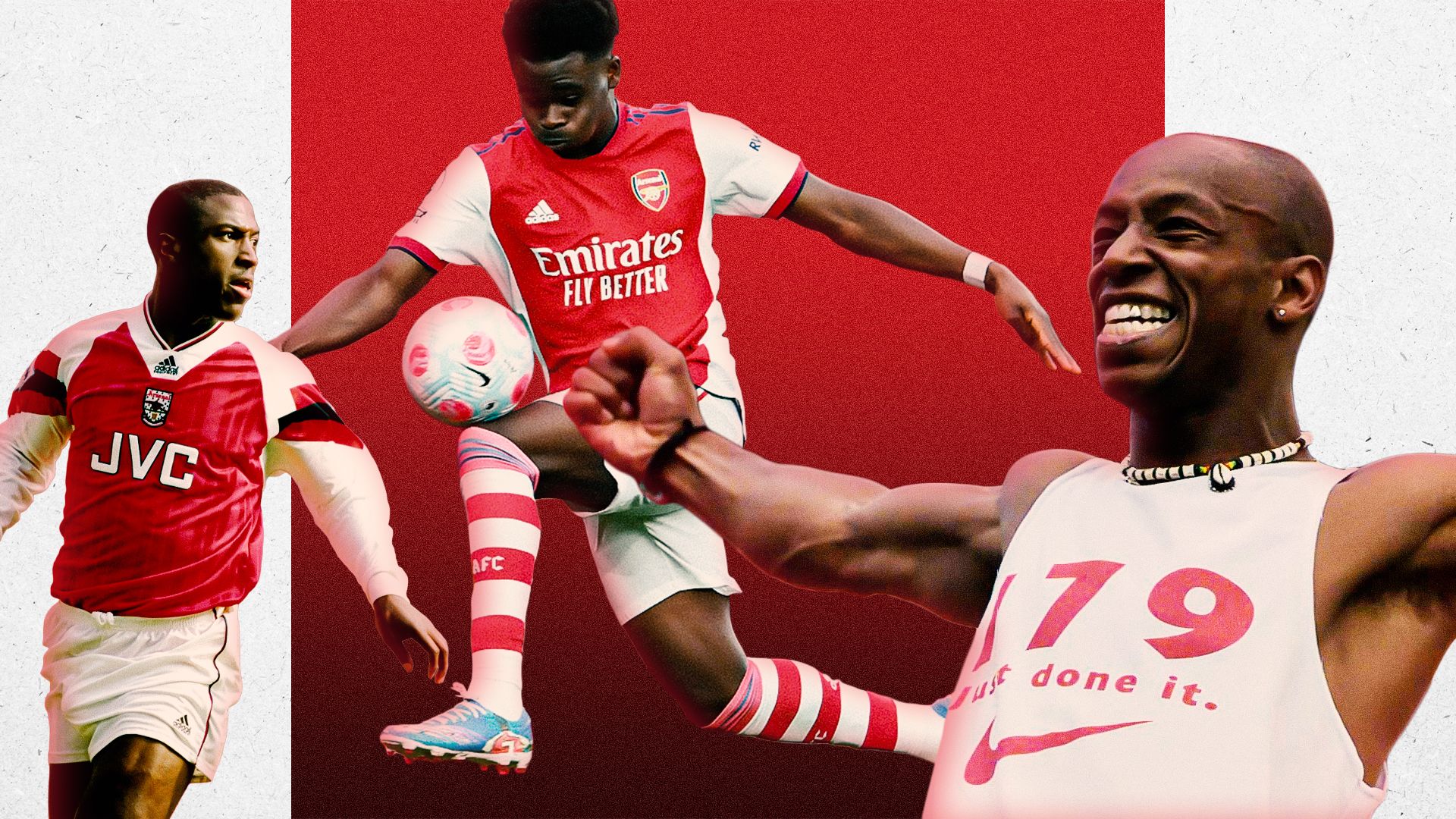

The players, though - from Brendon Batson, who became the first Black player to represent the club in 1971, to Bukayo Saka, the present-day talisman - are the protagonists, their visibility key to fostering the sense of belonging which has drawn so many Black supporters towards the club and helped develop its multicultural fanbase.

Nwonka is eager to highlight the trailblazing role of Davis in particular.

Paul Davis, Michael Thomas and David Rocastle celebrate a League Cup win over Tottenham in 1987

Paul Davis, Michael Thomas and David Rocastle celebrate a League Cup win over Tottenham in 1987

"For me, he is the one who really makes a difference because he joined in the late 70s from south London and, while Batson had to go to West Brom to make his name, Davis stayed in the first team for 15 years and made more than 400 appearances.

"He is someone who spanned the core periods of Black Arsenal, from the late 70s to the mid-90s, because he made it through from the academy when others didn’t.

"That allowed for David Rocastle and Michael Thomas to think, 'We can do it because you did it', which then allowed for Campbell and Ian Wright to come to the club, which then allowed for Thierry Henry and Saka, and so on.

"So, I think it really began with him in the late 70s. That was a conduit for everything else that happened, which influenced fan culture too. Black people could go to the games and see something they recognised.

"That builds and builds into what you see today."

"I had not recognised when I was playing for Arsenal that the work I did on the pitch and off the pitch meant so much to Black people. Knowing this is worth more than my two league title medals. I truly mean this. Because it's the Arsenal. I'm part of this club, and the club is part of me."

For Davis and other young Black players emerging during the 1970s and 80s, there were of course huge contextual differences culturally and politically.

The National Front was in its heyday. Black Britishness was still contested. In Black Arsenal, Davis describes racist abuse from the terraces being the norm for visiting Black players at many away grounds.

"Paul talks a lot about coming through as the only Black player from the youth team at Arsenal but not really experiencing any racism within the club, apart from one or two loose comments or jokes which had to be dealt with," says Nwonka.

"That is quite remarkable in the context of that period. I’ve heard really horrific stories of amazing young Black players who didn’t make it through academies just because they couldn’t stand the abuse they received, often within their own clubs.

"It was different for Paul and others at Arsenal. When it came to the abuse he received at away stadiums, his approach was, 'If I throw the towel in, it’s on me. That’s me done. I’ve got to withstand this'. It’s a testament to his stamina and mental and emotional fortitude that he was able to do that."

Davis, together with Rocastle and Thomas, fellow Black south Londoners and graduates of the club’s youth academy, would go on to play a key role in Arsenal’s First Division title wins under Graham in 1989 and 1991, the first of which was secured by Thomas’ iconic stoppage-time goal at Anfield.

Michael Thomas scores Arsenal's title-clinching goal at Anfield in 1989

Michael Thomas scores Arsenal's title-clinching goal at Anfield in 1989

It is a moment which still pains Nwonka, who grew up in north-west London but supported Liverpool and idolised John Barnes. "I watched it a hundred times during my research and I’m still convinced something is going to happen and he’s not going to score," he smiles. But he appreciates its huge significance.

"What it symbolises is everything that Black Arsenal is now, which is the transition from the old First Division to what would become the Premier League, with Sky Sports, which was intended to market the sport in a particular way and turn it into a spectacle for a mass audience.

"I think the Premier League was born from those moments, where you had 12 or 14 million people watching this incredible drama.

"And on top of that, the main protagonists were Black. Not just Mickey Thomas but also Rocky Rocastle, with his fist-clench after winning the free-kick for the first goal, and John Barnes, losing the ball in the lead-up to Arsenal’s second goal.

"What happened afterwards was the explosion of the Premier League, where the visibility of all players becomes magnified by 100.

"But you wonder, without the drama of that goal by Mickey Thomas, whether there would have been the same impetus to create the Premier League as we have it now."

Thomas and Rocastle had left Arsenal by the time the Premier League launched in 1992.

In Wright, though, another Black south Londoner, signed from Crystal Palace a year earlier, the club had acquired a player whose impact, in a cultural sense as much as a sporting one, would be even greater.

"When he emerged, it was very, very clear that he had a different kind of personality and approach to the game," says Nwonka.

"Of course, television helps. He arrives in 1991, does well, and then the Premier League happens and he is a poster boy for that.

"But also, his whole demeanour was very recognisable to a lot of working-class people, Black or otherwise, who appreciated his journey and the way he behaved on the pitch."

Nwonka draws a comparison between Wright, with his uninhibited emotion, and the more restrained Barnes.

"John Barnes was someone I adored as a kid but he had a different approach, different behaviour and mannerisms," he says.

"Of course, he was quite famous for anti-racism and I recognise that as well. But Ian Wright just had a different kind of rigour to the way he approached questions of identity."

Soon, Wright had become the face of huge Nike advertising campaigns. Nwonka also highlights the cultural significance of him celebrating goals by doing the Bogle, a Jamaican dance invented in the 1990s and popular in reggae and dancehall music.

"When you’re in the Black urban enclaves, that’s recognisable," he says.

"You go to the barbershop and senior men are talking about Arsenal, Ian Wright and Kevin Campbell. As a young Black person, you want to be involved in those conversations. It was part of your learning."

The impact of Wright's demeanour and behaviour is a theme of the book. Arsenal fan and podcaster Clive Palmer writes: "Ian's message was: 'I'm not shy – I'm not going to change who I am to be at an elite club.'

"What he did, without realising, was give us all confidence that it was OK to be you… You don't have to fully conform to blend in."

Photographer Eddie Otchere, meanwhile, describes Wright as Arsenal's "rude bwoy hero front and centre", adding: "My love of the Arsenal is entwined with my love for Ian Wright, the flash of the gold tooth in his grin, as he curls over laughing at his own joke."

"There is my generation of Black Arsenal. And here is a new one. Saka, he's now the star boy. I'm just pleased that when you go through our history, Brendon Batson, Paul Davis, Chris Whyte, Rocky, Mickey, me, Patrick Vieira, Thierry Henry, there is always somebody who is championing us."

- Ian Wright in Black Arsenal

Arsenal’s Black connection continued to grow under Arsene Wenger, another milestone coming in September 2002, when they became the first English club to field nine Black players in a game.

An Arsenal team containing Lauren, Ashley Cole, Kolo Toure, Sol Campbell, Gilberto Silva, Patrick Vieira, Sylvain Wiltord, Nwankwo Kanu and Henry, as well as David Seaman and Pascal Cygan, subjected Leeds to a 4-1 thrashing that day at Elland Road.

Nwonka points out that, as with the growth of Black Arsenal more broadly, the make-up of the side that day felt completely organic.

"Arsene Wenger didn’t pick nine Black players to make a statement," he says. "Those were just the best players at his disposal.

Arsenal players celebrate during their 4-1 win over Leeds in 2002

Arsenal players celebrate during their 4-1 win over Leeds in 2002

"People often ask me if I think Arsenal, as a club, cultivate this kind of Black identity and I always say not really. Of course, they recognise it now and they do things to harness it..."

Nwonka uses the example of this season's black, red and green away kit, made by adidas and designed by Foday Dumbuya, the founder of menswear brand Labrum, which is intended as a tribute to African icons such as Kanu who helped cultivate the club's large African fanbase.

"But Black Arsenal has always been about how Black people move to Arsenal, rather than Arsenal moving to Black people," continues Nwonka. "I think we often flip and confuse it.

"If anything, I would like them to not package it so much. That is probably oxymoronic given I’ve done the book, but the point I make is that it doesn’t need to be hyper-marketed or celebrated because it is going to happen anyway, regardless of whether you make Jamaica away shirts or Arsenal Africa shirts.

Bukayo Saka wearing Arsenal's 2024/25 away kit, which celebrates their iconic African players and their fanbase

Bukayo Saka wearing Arsenal's 2024/25 away kit, which celebrates their iconic African players and their fanbase

"I think the Black connection is something you need to acknowledge and appreciate, but it’s also something you can give space to because it's always going to be there, to the point where you don't even really notice it.

"When you go to the Emirates Stadium as a Black person, you're not consciously aware that you’re in a stadium with a lot of Black people who you wouldn’t normally see at games or sporting events elsewhere.

"It's just what it is now and that’s the beauty of it."

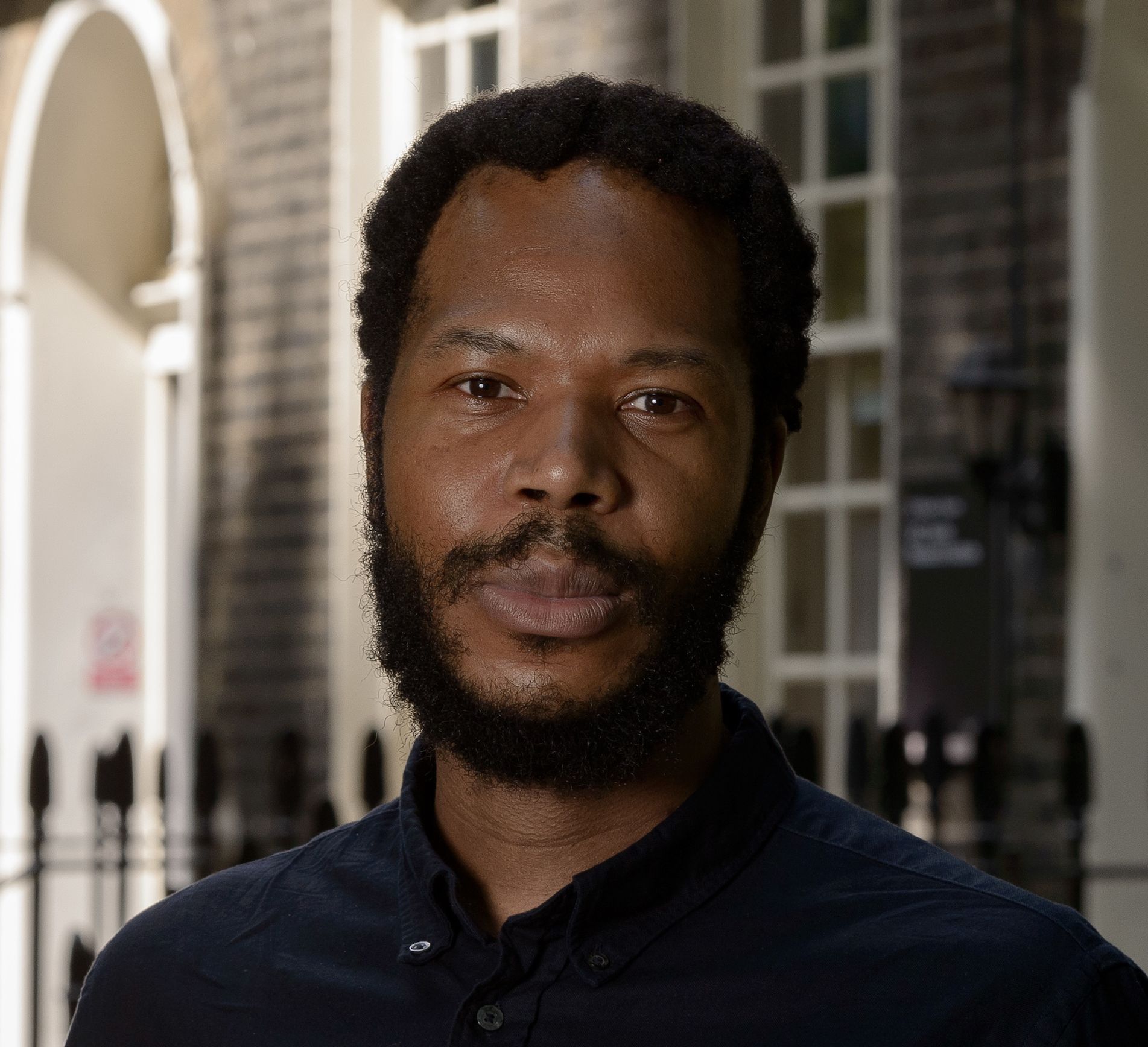

Clive Chijioke Nwonka is an associate professor at University College London

Clive Chijioke Nwonka is an associate professor at University College London

Black Arsenal makes no claim that Arsenal are uniquely responsible for driving social integration in English football, or that they are a perfect institution when it comes to the issues of race and representation.

The club's women's team have a history of fielding Black players, including Alex Scott, Anita Asante and Rachel Yankey, but there was outcry last year following the publication of a squad photo which showed a lack of Black or ethnic minority players or staff, an issue Arsenal acknowledged at the time.

"I don’t think that was a consequence of any malpractice or wrongdoing on Arsenal’s part, in terms of the playing staff," says Nwonka.

"But I think the reason it stood out is because, as a society, and given the club’s history, we expect more from Arsenal.

"I think that is something that should be embraced, and I think Paul Davis makes an excellent point when he talks about the next phase of Black Arsenal, in his mind, which refers to the things we can't see, so the infrastructure, the boardroom, those in stakeholder positions."

It is a reminder of the work still to do, at Arsenal and beyond.

For now, though, it is worth celebrating the progress already driven by the club, and by the long line of players who have helped to forge its unique Black connection, from Batson, Davis, Rocastle and Thomas, to Campbell, Wright, Henry and Saka.

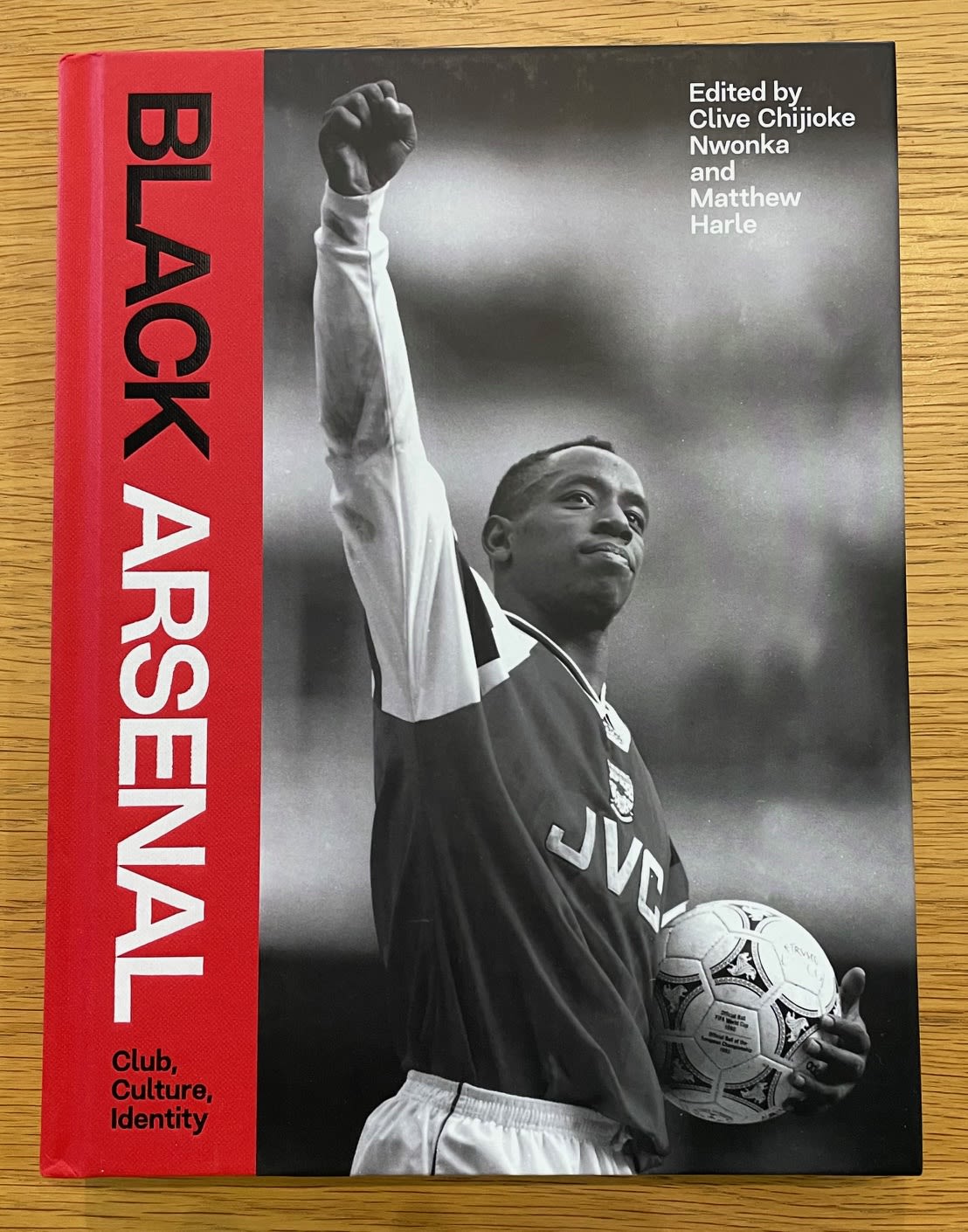

Black Arsenal, edited by Clive Nwonka and Matthew Harle, is out now from W&N